The first stop was the Trinity Church Cemetery of Upper Manhattan, which is associated with Trinity Church on Wall Street in Lower Manhattan. In the mid-1800s, Trinity Church ran out of room to bury people in Lower Manhattan, so this Washington Heights cemetery became an extension.

Among the people interred there are Ralph Ellison (Invisible Man author), Clement Clarke Moore (who wrote "Twas the Night Before Christmas"), Jerry Orbach (Law & Order just wasn't the same without him), Alfred Tennyson Dickens (one of Charles Dickens' sons, who died in NYC's Astor Hotel while participating as guest of honor in the Dickens Centennial), and John James Audubon, whose tombstone unsurprisingly features different kinds of birds.

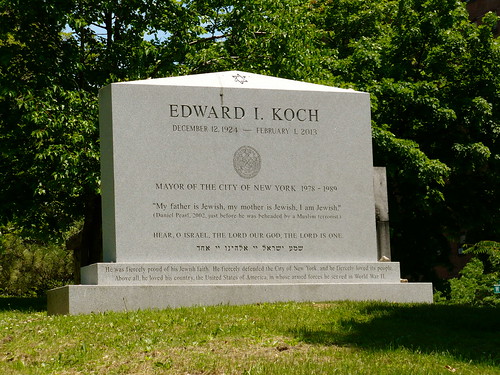

Former NYC mayor Ed Koch, who didn't want to leave Manhattan after death, also secured a burial spot here; the cemetery is non-denominational and the only active one in Manhattan (though at this point, people can arrange to get interred only above ground in a mausoleum). Koch is buried near an entrance to the cemetery grounds called the Jewish Gate.

The stone has a verse of the Shema Prayer inscribed on it, "Shema Yisrael," which is of huge significance to Jews; even those who aren't particularly observant often know these words and recite them.

Also, Koch chose to inscribe the final words of journalist Daniel Pearl on the tombstone. It surprised me when I first saw it. Part of what it conveys to me is that Koch saw his Jewishness as central to who he was not only in times of peace but also in times of war and persecution (for instance, he had served as an infantryman in Europe during World War II). He had specified what he wanted on his tombstone before his death, and interestingly, he wound up dying exactly 11 years after Pearl - on the same date (February 1st).

Prior to seeing his tombstone, one of the people in the group jokingly wondered if it would have his slogan, "How'm I doin'?" inscribed on it.

A fortunate twist to our visit there involved one of the cemetery security guards, who's in the military and currently in NYC studying for an advanced degree in military history. He walked with us for a while and told us a lot about the day-to-day operations of the cemetery (including what it's like to go into one of the crypts) and its history.

There's a marker commemorating Revolutionary War clashes that took place here following the Battle of Long Island in 1776; Washington had managed to evacuate his troops from Brooklyn Heights to Manhattan, where they went on a retreat up the island, fighting along the way.

The cemetery is on high ground overlooking the Hudson River, and one of the jokes people make here is about the excellent view it affords its residents. It's also a sprawling place, and a couple of times the walk leader accidentally took us down a dead end (har har).

Anyway, enough cheesy graveyard humor. There are many stories here in the names, in the words and symbolism on the tombs, and just in the general atmosphere. It's worth exploring if you're interested in history or are looking for a quiet place to walk.

The Church of the Intercession, which was for decades a Trinity Church chapel but is now independent, is on the grounds of the cemetery; it holds an annual Clement Clarke Moore festival where "Twas the Night Before Christmas" gets recited. The cloister is a lovely, quiet little spot to peek into.

From there, we headed east and stopped in Sylvan Terrace, wonderfully out of place in the city with its cobblestone street and wooden row houses from the 19th century.

People live here, but they're not allowed to change the external appearance of the homes, including the color scheme and the identical sets of 11 steps leading up to each door.

Sylvan Terrace is right across the street from the Morris-Jumel Mansion, and its cobblestone street used to be a carriage path taking you to the mansion, which was the setting for some interesting military, political and personal drama during the American Revolutionary War and in decades after.

In 1765, it was built by Roger Morris, a retired British army colonel who lived there for a decade. His home was confiscated and got turned into military headquarters for Washington in 1776, for part of that brief time Washington spent on the retreat in Manhattan before needing to give up on the island. After that, the British used it as a military headquarters for themselves.

Washington would come back here in 1790 for a celebratory dinner with guests that included a few future presidents: John Adams and his son John Quincy Adams, and Thomas Jefferson.

In 1810, the mansion was purchased by a wealthy French wine merchant, Stephen Jumel, and his American-born wife, Eliza, who after Stephen's death married Aaron Burr, the former Vice President of the US and the guy who killed Alexander Hamilton in a duel (a historical tidbit I first learned about as a child after watching this commercial).

At the time of their wedding, Eliza was in her late 50s and Burr was in his late 70s, and their brief marriage ended in a divorce that got finalized on the day he died. Eliza Jumel, who is buried in Trinity Church Cemetery, lived for decades more and reportedly developed dementia later in her life, dressing up for non-existent dinner parties. Among the many colorful stories around her is that she continues to appear as a ghost on the mansion grounds.

There's a lovely garden on the grounds of the mansion, which is the oldest home in Manhattan.

The mansion and its grounds, on their perch in the heights, look out on other parts of the city.

After the mansion, we headed west again, catching tributes to African American history and culture along the way.

There were a couple of small street fairs: One of them looked like an arts and crafts festival, and the other was a smaller gathering and had people singing in Spanish. (This was the Sunday of the Puerto Rican Day Parade, which I'd stopped by last year; the parade itself isn't held in the Heights though, but on 5th Avenue starting from Midtown and continuing through the Upper East Side.)

We ended the walk at the Audubon Terrace, where you'll find the Hispanic Society of America and a couple of galleries of the American Academy of Arts and Letters. Also, sculptures by Anna Hyatt, most notably her rendering of the 11th-century Spanish nobleman and hero, El Cid (Rodrigo Diaz).

Nearby, another Hyatt sculpture portrays Boabdil (Muhammad XII of Granada), the last of Spain's Moorish rulers.

Verses from a poem by Hyatt's husband, Archer M. Huntington, are inscribed on the base of the statue:

He wore a cloak of grandeur. It was bright

With stolen promises and colours thin,

But now and then the wind—the wind of night—

Raised it and showed the broken thing within.

I'll leave you with a quote to think about, from over the doorway of the North Gallery of the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

What do you think it means?